Narrow Road to the Deep North

Gallery ReviewSet in Japan during the late Edo period, the Buddhist poet Basho travels searching for enlightenment. He comes across a city ruled by a tyrannical overlord called Shogo, and manages to gain his confidence. As a result he is given the son of the emperor that Shogo overthrew to look after, and they leave the city, heading for the deep north. When he returns it is with the Commodore and his devout sister, who bring both Christianity and cannon…

This satirical play by Edward Bond may be a damning indictment of British Imperialism or a wider piece examining the morals and motivations of rulers, be they vicious tyrants or evangelizing colonisers…

Cast

Terry Brant

Simon Brant

Terence Richardson

Mark Poncia

Maurice Holdstock

Jane Briggs

Alan Clarke

Roger Keightley

Backstage

Roger Keightley

Disturbing images and powerful ideas

Reviewed by G M P for The Croydon Advertiser.

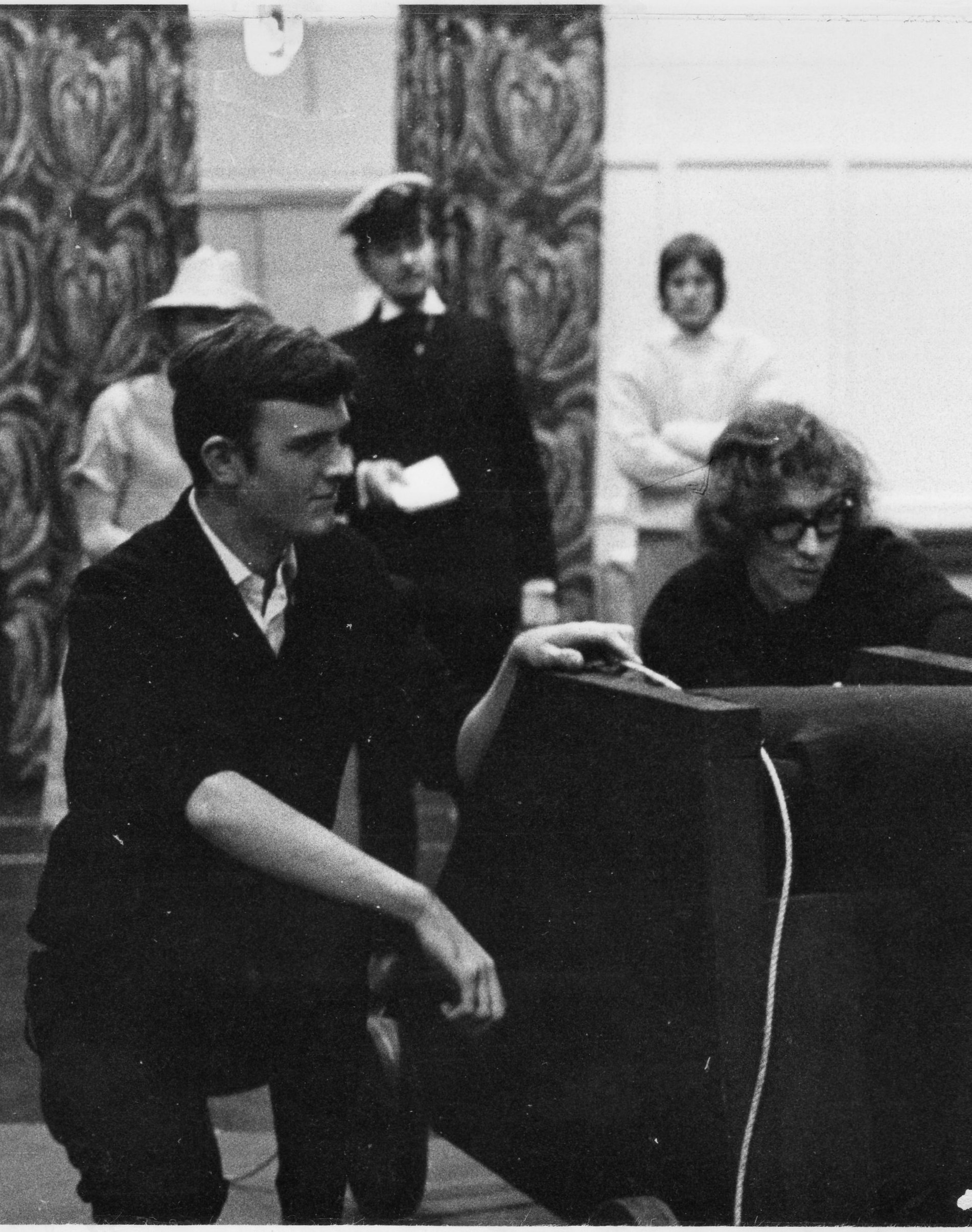

An extraordinarily stimulating theatrical experience was provided by Roger Keightley’s well planned production of Edward Bond’s “Narrow Road to the Deep North,” presented by Theatre Workshop Coulsdon for two performances this Saturday.

I choose the word “experience” with care, since what was offered had more in it than a casual two hours’ playgoing.

To begin with – and valuably – the company proved that they can operate inside an artistically controlled framework and harness to it the imagination and emotion they bring to their improvisations. Then the play itself is powerful and disturbing, using a series of fables, closely related to the perception-training koans or anecdotes of Zen, to pose large questions about man’s responsibility to man.

Its central figure is the young contemplative Kiro: the locale, Japan “during the 17th, 18th or 19th centuries.” On Kiro’s pilgrimage towards “enlightenment” all that he sees grieves his heart, but he only passively absorbs it.

Contrasted with him is the active brutality of the dictator Shogo (his ruthlessness bred, we learn, of a loveless childhood). His murderous coups to take and keep power bring him into conflict with the fatuous ‘Empah-building’ Commodore and his missionary consort Georgina (who might be his sister and might not.) She forces her puritan morality on the peasants to “protect them from themselves” and treats them like backward boys.

But when, in one of the play’s most moving scenes as played at Coulsdon, the class of actual children she is teaching to pray are brutally butchered by Shogo’s men, she can’t face the reality and goes out of her mind. Jane Briggs gave her autocratic fanaticism fire and urgency, and her Ophelia-like mad scenes were in admirable wild contrast. (It was an imaginative touch to represent the meekly kneeling children by simple rag dolls in this scene, their bowed heads and still forms giving great poignancy to the cruelty of the slaughter.)

It’s sad that space limitations won’t permit me to explore more of the play’s plentiful ideas. This is easily the most fascinating new work to come my way this season. It ends on a note of hope or despair, according to the point of view of the beholder. Disillusioned Kiro commits hari-kari just at the moment when a young man calls for help because he is drowning. But the victim saves himself without Kiro after all. Life goes on. And the unspoken question hangs in the air: “Must it always be so selfish and stupid?”

Mr Keightley rightly presented the piece quite simply – no distracting glamorous Oriental costumes and sets. His actors spoke the well written lines with clarity and point, and with an appreciation of the comedy where it was found.

Terry Brant, smiling inscrutably as the complacent poet-sage Basho, brought out well the smug self-centredness. he had to compete for the audience’s attention part of the time with his own infant son, Simon, who played the little Emperor, and whose wide-eyed baby interest in all that went on when he was on stage emphasised Bond’s pre-occupation with innocence too soon corrupted.

Terence Richardson played the inquiring Kiro with a rewarding absence of false histrionics, his facial reactions conveying the inward puzzlement and stress. The hari-kari with abundant “blood” was nastily effective. Stage haemoglobin spouted freely, too, when Mark Poncia as the tyrant Shogo met his comeuppance, the actor having characterised the role with furious drive and driving fury.

Of Jane Briggs I have already spoken: her “brother,” the hearty fool of a Commodore, was comically caricatured by Maurice Holdstock; and Alan Clarke, so often the energetic inspiration behind the group’s improvisations, gave a well disciplined performance in small-part appearances as soldier and peasant, though his vitality and good stage presence made him stand out from the crowd.

Roger Keightley himself appeared briefly as the new “hope” at the end of the play. Judging from this presentation, there’s even more significance in that than was intended.